The Reluctant Pioneers

You’ve probably seen all those viral videos on social media. Like this one of a gal who’s tricked out a school bus to live in. In one video she is lounging on a mattress, gazing out her back window into a forest. “I think a lot of people would pay a lot of money to have a view like this from bed. And I’m just so grateful that I have that.”

She has one and a half million subscribers. These adorable bus houses also have an adorable name. They’re called Skoolies. She even has a record player spinning in there. Or those itty-bitty tiny houses on Pinterest? Mini mansions on wheels? Don’t you just drool over their cuteness? It’d be like living in a dollhouse.

“This is a two-story luxury treehouse located in Canada. Would you stay here?”

Then there’s the hashtag van life movement, super popular with the Millennials who blog about their travels living in sporty camper vans. Or how about all those lucky folks moving into RVs – kids, pets, and all. Or the adventurers, like this one, who are buying cheap land and going off grid.

“I don’t have any bills now. I bought this little shed for $8,000. I made it into a house. Check out the inside.”

But I’m here to tell you, been there, done that. It’s not always as idyllic as all these videos make it out to be. Social media depicts this so-called minimalist life as a hypercool lifestyle choice. Maybe that’s even what I thought when I went off-grid. But I’m not so sure it is. Because all the videos belie something more problematic going on beneath the surface. An affordable housing crisis that’s affecting the working and middle class more and more. Lots of people are choosing to live in sheds and tents, and old mobile homes, because they kinda have to. Here’s a researcher at the Low Income Housing Coalition, Andrew Aurand.

“The general long-term trend has been that it's been increasing. And it's a shortage that impacts nearly every, if not every community, in the U.S.”

His organization compiled a study that shows that eight of the top ten states with the worst affordable housing shortages are in the American West. That means in those states there’s less than 30 affordable homes for every 100 people. That’s really affecting people who qualify as extremely low income because they’re at or below the federal poverty level.

“In Wyoming, for example, there's only about five affordable and available rental homes for every 10 extremely low-income renters.,” Andrew says. “So the supply is only serving half of the extremely low-income population. And in other states, it's even worse. So, for example, in Utah, there are only about three rental homes affordable and available for every 10 extremely low-income renters. And then in, just another example, it's even worse in Nevada, where there's less than two.”

And living with the threat of not having a home has serious ramifications for people.

“ People who don't have stable housing are more likely to be sick, they are more likely to feel exorbitant levels of COVID-19, of mental health challenges,” Andrew says. "And so it has impacts on health. If you are evicted and struggling to find stable housing, the probability of you losing your job goes up. Because it's hard to maintain your job if you're also trying to figure out where I'm going to live next week or even where I'm going to live tonight.”

But as Westerners, we were raised on ideas of pick yourself up, dust yourself off. ‘Okay, so there’s no place to live – guess I’ll just D-I-Y.’ Not so different from our ancestors. Like in this old Woody Guthrie song about a family struggling to survive that decides to pile their stuff into a covered wagon in search of opportunity.

“I've been a grubbin' on a little farm on the flat and windy plains

I've been a listenin' to the hungry cattle bawl.

I'm gonna pack my wife and kids,

I'm gonna hit that western road.

I'm gonna hit that Oregon Trail this comin' fall.”

Hitting the western road is still an allure for Americans. Almost half of the American West is public lands, available to live on temporarily as needed. It’s another reason why adopting a drifter lifestyle is such a big thing.

Those wandering drifters wouldn’t necessarily consider themselves homeless. I know I didn’t think of myself that way. And the federal government isn’t sure how to categorize us either. I recently went digging in the U.S. Census data and found that in 2020, a brand new category was created for people who live in vehicles, motels, sheds, tiny houses, yurts, stuff like that. “Transitory situations,” these people’s lives are now officially called. I talked to Ryan Mitchell, who calls this life something else. Ryan is the founder of the website thetinylife.com, a hub for people considering off-grid lifestyles like homesteading and tiny homes. He lived in a tiny house for several years – we’ll hear his story in a future episode. Ryan says he prefers the term a minimalist life.

“It's a way to kind of orient your life towards the things that you want to maximize and then also at the same time, kind of making adjustments to it to minimize the things that maybe you don't want to make so much space for,” says Ryan. “That could be physical things, that could be a mental clutter, that could be your schedule, all sorts of kind of iterations of that. So when you get to it at the end, it's maximizing what you want, minimizing what you don't.”

The main thing he wanted to minimize when he built a tiny house was the number of bills he had to pay. Ryan says he can always tell when the cost and availability of housing gets worse. He uses the number of visitors to his website as a barometer.

“It's an interesting dynamic because whenever the economy isn't great or housing kind of ratchets up in cost, we see growth,” he says. “In a weird way, we benefited from all that change. But I can kind of have a pulse on what the collective consciousness is around housing and costs and cost of living and things like that, just by looking at my traffic metrics. When it surges, when it ebbs.”

In other words, when housing costs gets really bad, more people go off grid. The U.S. Census found that, in Arizona, almost 12,000 people live in these transitory situations. Here, in bitterly cold Wyoming, almost a thousand. New Mexico and Colorado have over 2,000 living in between worlds in those states. And that’s just the number of people they could track down – the Census admitted it was a very difficult category to count. You can’t call these people unhoused, but they aren’t housed exactly either. I talked to a guy at the Wyoming Community Development Authority about this quandary. Chris Volzke is his name. It’s an organization trying to address the lack of affordable housing here in Wyoming. Talking about the problem, he has trouble not getting hyperbolic.

”This is a hard statistic to even fathom but it's real,” Voltzke says. So the median household income in Wyoming, which is a little over $70,000 a year, right? Cannot afford the median-priced house in every county in the state without being cost-burdened.”

And as we heard earlier, Wyoming isn’t even the worst in the American West. But Chris says part of the problem is just a matter of how we think about the people who aren’t able to keep a traditional roof over their heads.

“ The majority of homeless people in Wyoming are Wyomingites.” he says. “It's primarily our neighbors and people in our community that had a series of events that forced them out of their rental into a car, into the street, whatever the scenario is.”

Here in Laramie, I’m seeing the effects of these statistics almost everywhere I look. Someone living in a motor home at one of my favorite trailheads. A family living out of a couple buses, an electric cord stretched across the sidewalk. Another woman living out of a camper on the street. An elderly man and his dog living in his car in a parking lot. An RV with a water tank and playground equipment in the middle of the prairie. It’s hard to know what to think about all this. Are these adventurers? Or should I be worried? I decide to ask.

Josh Watanabe is the director of Laramie Interfaith, a nonprofit that works to eliminate food insecurity and homelessness in my town. He says I’m not imagining things. He’s seen these families too.

“ We do have clients that they're living in Medicine Bow National Forest this past summer in a tent because you can camp in our national parks, that's what they're there for,” says Josh. “It wasn't by choice. They just couldn't camp in town, and that created that extra hardship because the father was looking for work. But he would have to drive 20, 30 miles to get to the campsite to come in for a job interview and to work. And of course, they didn't have the utilities. So when you show up to a job interview and maybe haven't showered in a while, clothes are wrinkled or you smell like campfire smoke, you're not gonna be the first choice at that job.”

Josh says it can get dangerous in the winter, too, when people try to warm themselves with candles in their car or start a wood fire in their camper. Albany County where we live has the worst gap between rental availability and the rental need in the state. Sure, that has everything to do with the fact that we have the state’s one and only university here with lots of students looking for cheap rent. But still, Josh says they’ve seen a huge increase in the community’s need, just in the last year.

“We are well above capacity when it comes to our client services, rental case management, utilities assistance, there's more people who have a need than we're able to help,” says Josh.

And when people are spending all their money trying to pay rent, that leaves less money for food.

“We will have moved and brought through this building over 450,000 pounds of food, which is a over one-third increase over past years,” says Josh. “We are serving, over the course of this year, I think we will serve 1,300 households. That's a huge increase.”

In Wyoming and across the American West, we might see families living in a tent as rugged individualism. But that attitude concerns Josh.

“We've romanticized this idea of being independent,” Josh says. “Just like the cowboy myth and everything else. It's a part of what we believe that isn't quite real. It's one thing I think to maybe go out west and create a homestead in 1880 and not be so worried about a doctor when, okay, well, the doctor is really just gonna pour some whiskey on it and amputate your leg, right? The healthcare was different. Now, when you do so with the knowledge of saying, well, I'm not gonna have a doctor, but also, oh, I broke my leg, or, I'm having a heart palpitations in the middle of the woods. But I know that there's actually a solution to this, I think that affects our psyche a little bit different.”

But he says he sees our American mythology glamorized by social media and television.

“I think there's this survival show stuff that keeps popping up, right?” says Josh. “People who are gonna go out and homestead and build their own cabins and live off the land. And there are a lot of people that are able to do that too. And that's great. If you have the skills, the knowledge, you have the grit and the determination to go out and make a hard life and make it easy for yourself, then that's great. Where I draw an issue with this is the idea that this is a solution to our housing crisis. Because it's absolutely not.”

Still, lots of people are hoping an off-grid lifestyle could work for them. That they can be the exception that proves the rule. I know that feeling. Back in the late 90’s when the cost of housing started to pinch, my husband and I went off-grid as our affordable housing solution. I recently sat down with my husband Ken Koschnitzki and we pulled all our old photo albums off the top shelf and took a little trip down memory lane.

Ken and I take our albums off the shelf and start paging through them. We’re shocked how little of our photos cover the era of our life when we lived in a tent. Back in college in the 1990s, both Ken and I were on our own to pay for everything. I had some good scholarships and grants but they didn’t cover housing. Ken even waited until he was the age of emancipation to go to college so he could get federal grants. But that meant we lived as cheaply as we could.

Ken says, “We had that studio that was $210 a month. Super cheap.”

“It was basically a back porch that they just like, put a kitchen in,” I say. “I mean, our bathroom in there was like…”

“You couldn't close the door if you were in there. Yeah, your legs stuck out.”

At first, it was pretty easy to find cheap places like this to live in cities like Durango and Fort Collins. But by the time we moved to Flagstaff in the later 90’s, it was getting harder to find affordable housing. We got a duplex just outside of town for around $800 a month.

I say to Ken, “We were in this pretty okay apartment, but I felt like it was too expensive, and we had this money burning a hole in our pocket, and I was supposedly writing a novel. I did not want to work any more than part-time. And you were going to school.”

We had some money we’d saved up. And for years, we’d dreamed of buying a little piece of cheap land. We’d traveled all over the U.S. looking at places.

“We bought that book,” Ken says, “Finding and Buying Your Place in the Country, and talked about riparian water rights on the East Coast versus the West Coast water rights. So yeah, we were being very idealistic, and I don't know how we were thinking we were going to pull it off. But then we did! Kind of.”

So when we moved to Flagstaff, we couldn’t help ourselves. We kept looking.

“I wanted to paint and you wanted to write, and so we thought that that was the avenue to freedom, artistic freedom, was to just have land, basically,” says Ken.

“So then we started going out and looking at Alpine Ranches because that was super cheap land,” I say.

“Yeah, I mean we found an ad,” says Ken. “We would scour the newspaper, classifieds, this was pretty much pre-internet, I think. Yeah, and it was like, a thousand dollars an acre. And ten acres to fifteen acres.”

Alpine Ranches was dry desert land amongst volcanic craters on the edge of the Navajo Nation. All covered in pinyon and juniper trees. It had once been owned by the railroad in a checkerboard pattern with BLM land. So you could buy property abutting public land, which was our dream. But other aspects of Alpine Ranches weren’t so dreamy.

“So Alpine Ranches, when we first started looking at it, was the wild west,” says Ken. “Literally people would get in gunfights out there. And like, somebody got shot in the gut, so it had its own kind of like, set of rules. We had some really nice neighbors, some frightening neighbors.”

We bought 10 acres in the bosom of two large craters for $10,000. To go from paying $800 a month to $100? It felt like a no-brainer. But there was no water, no power, no nothing…unless you counted our 75-mile view of the Painted Desert.

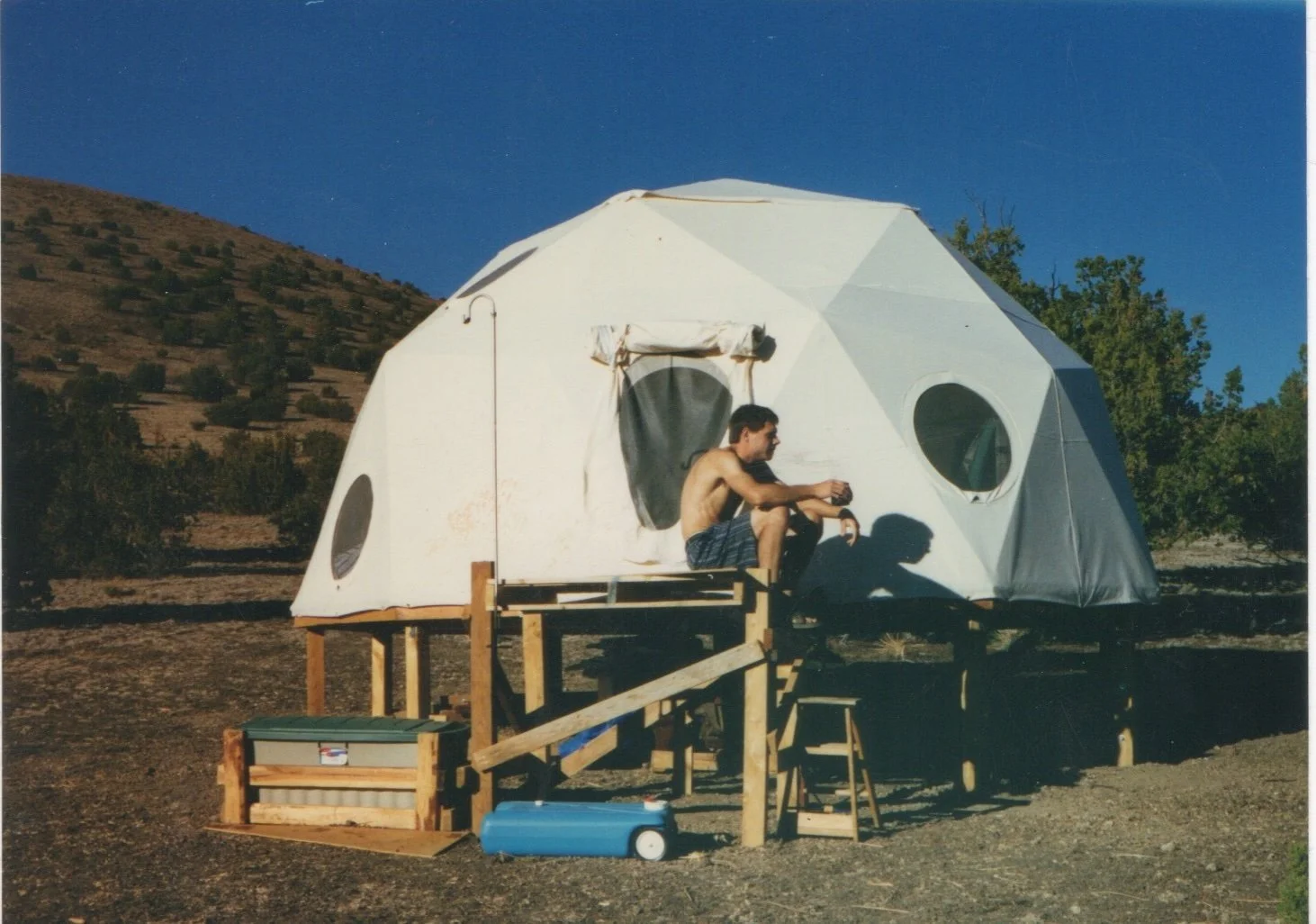

We set to work building a platform for our canvas geodesic dome.

“ It was a 17-foot dome,” says Ken “It had a eight and a half foot ceiling and we put it on a two-foot wall. So it was 10 and a half feet, and we had a loft bed.”

“We had to climb a rope ladder to get into our bed like monkeys,” I say.

“But we had insulated it with Reflectix and plywood on the inside.”

“Yeah, so it felt like it had walls on the inside.”

“But it was canvas on the outside, with windows that were plastic, that could pop out.”

“Remember that time that we were laying in bed?” I say. “And there was a crazy storm and like our faces were like a foot from the ceiling and the wind was just beating our canvas. And then the window right by our faces blew out. We had to jump out of bed and go running around in the desert looking for our window?”

For our kitchen, we hauled out a family camper trailer. It had a propane heater and cookstove. For water, we used five-gallon camping jugs with spigots. In the morning, we’d tromp outside to the little trailer and put on a teapot for hot water to wash our faces and armpits before we headed out to work and school.

We find a photo of us in our camper.

“We look cold, though, don't we?” I say. “I’m at least not wearing a hat in my kitchen. Like, I'm just all bundled up in, like, big sweaters. And you've got thick flannel.”

For power, we coughed up some money and bought a wind generator.

“ In Flagstaff, there was a home wind generator manufacturer,” Ken says. “And one of the guys that worked there lived out at Alpine Ranches. And he would just steal parts over the course of like a month or whatever, and then assemble them and then sell them on the cheap. And I think we bought ours for $250, and they normally went for like $800 or $850 or something.”

But the generator didn’t give us much power. We could have an LED lamp in the evening or we could watch half of a black and white movie. But not both. Mostly we used kerosene lamps for light. I still keep our old Aladdin lamp on our mantel.

“Maybe we were an extreme example of it, but it's almost like we were homeless on our own land in a way,” I say.

“Totally.” says Ken “ Why did we think a tent would be a good idea? You know, I mean, we bought the dome for $1,500 bucks.”

“It came in the mail. Our house came in the mail.”

“But why did we go that route instead of just building a house? I mean, we didn't probably have the cash to do it. But, yeah, living in a tent, you're pretty much homeless.”

We lived in a glorified tent for almost four years. And sometimes that wasn’t safe. We could lock the trailer but the dome only had a zippered tepee-style door.

“Our nearest neighbor, Larry, had built his own house, says Ken. “He was a mechanic at a toilet paper company, essentially. He was a terrible, terrible alcoholic, lost his family. I think he had a kid. It was a pretty nice house. It had a loft, some stonework. But he had two serious accidents while he was there.”

The first time Larry fell off his loft he drove himself the 45 minutes back to the hospital in Flagstaff. The second time, he luckily had an old school cell phone, and they airlifted him out. Stories like this out in Alpine Ranches were a dime a dozen. Our other neighbors were Gary and Theresa. They’d built a traditional hogan and sweat lodge, and she worked for their tribe as a college recruiter. They helped us out a lot when we had a serious car accident driving into town one morning. We hit black ice and rolled our truck. But we couldn’t afford a new one. So we scrounged up another truck of the same kind with a bad engine and Gary helped us swap out the two engines using their hoist. This is the kind of DIY approach to life everyone took at Alpine Ranches.

“We did it kind of quick,” says Ken. “Like, it only took like a week or a weekend. It was fast.”

“He helped us, and so then he had some calves, and we watched his calves and fed them and watered them for a few days when they were away,” I say. “We had a nice neighborhood, actually.”

The economy out there was a kind of bartering system. You scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours. Then later, both Larry and Gary helped us move a shed onto our land. It was insulated and had a window and Ken used it as a painting studio. We bought it from these sketchy neighbors up the road. One time, driving around in search of a hike, they’d met us at their gate with rifles. Now they seemed friendly enough though. They only charged us $200 for the shed. But moving it proved a challenge. We tipped it onto Gary’s trailer but that lifted the back wheels of the truck off the ground. So we towed it in four wheel drive onto our land like that. And that’s when these two neighbors got a look at our other engine sitting in the back of our totaled truck.

“And so then you got a phone call from Gary.” I say.

Yeah, he said, ‘Yeah, somebody just stole your engine out of your pickup truck,” Ken says. “And that's when we called the cops and they were like, ‘Man, what can we do about it?’”

“So yeah, it was just lawless out there. It was a very lawless land.”

As soon as I told the cops where I lived, I could tell they stopped being interested. There were no road names in Alpine Ranches. Barely any roads. We were on our own with no social safety nets. Totally dependent on – and at the mercy – of our neighbors. Sure, it was great that no authorities were poking around to see what our septic system was. In our photo album we find a picture of Ken using our so-called outhouse.

“ And here you are sitting in our outhouse,” I say.

“Without walls. It was just basically a pit toilet with no house around it,” says Ken.

“You had a 75-mile view of the Painted Desert every time you needed to go to the bathroom.”

It was a no-man’s land. Sure, it was cheap. But was it worth it?

“I had so much stress every single day.” says Ken. “Like, I was in school, and I remember waking up one morning to go to school, and I just remember looking up at the truck, and the headlights were on, and I was just like, what? And I went up there and the battery was just totally dead. And so, I couldn't go to school that day.”

It’s been getting to me…seeing all the viral videos and hashtags glorifying the back-to-the-land life. Alpine Ranches wouldn’t have looked so adorable on Pinterest. But it was a beautiful life. Just not in the traditional sense.

“Your life was partially outdoors,” I remember with Ken. “Like a lot of it was about that landscape that I think was such a major benefit to that lifestyle that it made it almost worth all of the pain and stress of that lifestyle. Just like the sound of ravens flying over all of the time and seeing road runners run across the road. And remember that time that we were driving into town and there was a storm – like the storms were amazing – and we saw lightning hit a tree right in front of us and burst into flames?”

There’s so much I miss about that life. Flocks of blue pinyon jays…archaeology scattered across your property…sunsets like you wouldn’t believe…

“How do you think it affected who you are now?” I ask Ken.

“I mean, I grew up,” he says. “I mean, I have mad skills, you know. You just figure it out one step at a time, the way to build stuff. And that's lasted with me for sure.”

“I mean, we bought this old house and you fixed it up, building on the skills that you had honed from living on our land,” I say. “It feels like this house is kind of an extension of that lifestyle. We had the chickens, and we had the garden, and we have the greenhouse. In fact, the greenhouse is our dome that we lived in, which is pretty cool. And we've grown a lot of food in it now.”

“Well, and when we moved to Laramie, we didn't buy the cheapest house, but we bought the second cheapest house.”

“We were still aspiring to keep it cheap so that you can live a little freer lifestyle. Yeah. I don't feel regret about that time of our life.”

“Well, I wouldn't want to do it again,” Ken says.

“I kind of do.”

“I would do it differently.”

“What would you do differently?” I ask.

“I think I would have a structure. I mean, I wouldn't move back to Alpine Ranches, there's no way.”

“Yeah, I don't know that I would live in Alpine Ranches again either.”

So it seems there is a need for a sort of anti-Pinterest perspective of this lifestyle. To try to bring the so-called “transitory situations” that are people’s actual lives out of the shadows into the light. Because would I have rather bought land with a flowing stream and a legal driveway? Been able to install a septic system? Invested in a solar array? Absolutely. But I couldn’t afford those things. I also couldn’t find affordable housing. It’s a rock and a hard place that lots of westerners are caught between right now. So some people are refusing to pick between A and B. They’re opting for something totally different…and a little wacky. Instead of choosing debt, they’re using ingenuity to live close to the land. These are the voices of strength but also heart ache.

“ I was in Denver visiting a doctor, an oncologist, and her intern we were discussing how I snowshoe in and out, and this poor girl was like ‘You’re snowshoeing in and out in the winter?’ And I said, yeah. And she goes, ‘You can't drive to your house?’ I said, no. And she said, ‘Well, what do you eat?’ And it was like, ‘Well, we don't live on roots and berries.’” one homesteader tells me.

They’re honing mad skills, as Ken put it, so they can survive an era when so many are getting left behind.

“That was my first time using a saw mill,” says a young woman building her own strawbale house. “That was my first time rolling logs around, and just like actually putting it all together. I'm really proud of it.”

“We went searching for lodgepole pines to make the rafters,” my brother remembers. “They all had to be the same exact size and dimensions, more or less. Hand tools for the most part. I went and bought a draw knife, which I still own, to be able to strip the bark off of stuff and to carve stuff down a little bit easier.”

This season, we’ll meet these resilient off-gridders across the west, visit them where they live.

“That was one of the first things I did is upgrade the solar power because my daughter's on, she has to take oxygen occasionally, but she's on like a CPAP machine, and there's some other things,” says a single dad living off grid in an old 70’s trailer.

These are modern-day pioneers…reluctant pioneers…making do the best they can.

“It was go time right off the bat to try to survive through that winter,” a guy living in his RV tells me. “I changed the oil on one of my generators like one o'clock at night in a snowstorm in my jammies. You know, you're out there bundled up and trying to get things going again. So I had to laugh about that.”

We’ll hear their advice for going off-grid, and find out why this choice just makes sense to them. And for some people, like my own brother and nephew, why they’d never, ever do it again.

Music Attribution:

WORDS by Jason Shaw is licensed under a Attribution 3.0 United States License.

Blues and Tooth by Ethos is licensed under a Attribution 4.0 International License

Free Guitar Walking Blues (F 015) by Lobo Loco is licensed under a Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The Everlasting Phase by Patrick Davies is licensed under a CC0 1.0 Universal

MINSTREL by Jason Shaw is licensed under a Attribution 3.0 United States License.